The cities' contribution to war - urban warriors of medieval Sweden

Though small in number, Sweden's 16th-century urban population contributed significantly to military conflicts through their superior equipment. Let’s see how city-dwelling burghers transformed from merchants to warriors and how I recreated these troops in miniatures.

Burghers argue with a nobleman about how to conduct the attack. Siege of Kalmar, 1507.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Sweden was a sparsely populated country in the periphery of Europe. Perhaps, to no one's surprise, the urban population in Sweden at the time was less than impressive. Out of a population of at most 700,000 (including Finland) only some 31,000, four percent, lived in cities. By far the largest was Stockholm which had around 5,000 inhabitants at the end of the 15th century and probably more than 8,000 in the middle of the 16th century. This was two or three times the size of other large cities in Sweden at the time, like Kalmar and Åbo. Compared to other cities around the Baltic Stockholm was not that impressive though. Copenhagen had around 10,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the 16th century and Lübeck’s population exceeded 25,000 at the same time.

As with the peasantry, the burghers of the cities were expected to serve in military endeavours, not least, to protect their own cities. After negotiations with state officials, the peasants were paid for supplying troops by tax exemptions. Unfortunately, we do not know of any similar arrangement for the cities but obviously they considered the expenses of supplying troops to be a good investment. For example Stockholm continuously supplied soldiers and ships from 1502 to 1511 to be used by the regent at the time.

Mustering and organising the burghers

The cities and their burghers were active and willing participants in the wars waged during our period. They were not just passive players waiting behind their walls to be attacked but mustered, equipped, led and sent troops all over Sweden and the Baltics. Just as for the peasantry a number of burghers would group together to equip a soldier and just as for the peasantry men from their own ranks, like mayors or councillors, would command the troops. Most often the troops consisted of the burghers themselves but unlike the peasantry the burghers had the opportunity to pay a fee to the city who would hire troops to serve in their place. Unfortunately we don’t know how troops from the cities would be organised in the battlefield, if they formed their own units or were combined with other troops. Based on their equipment (see below) it is reasonable to believe that they would be placed among or organised with the nobility. One example of this would be a storming of the beleaguered city of Kalmar in 1507 where both the nobility and the burghers were expected to participate - unlike the peasantry.

The forces would be quite small though as the number of men mustered would be proportional to the population and wealth of the city. The smaller cities with a population of less than 700 could rarely muster more than a dozen men. The larger cities with populations reaching up to 1500 could muster several dozen. Stockholm could regularly muster 100 or more men. Martin Neuding Skoog concludes in his “I rikets tjänst” that the combined troops of all the cities constituted at least 500 men, probably more. This can be compared with the nobility who could muster around 500 men in total or the peasantry who could muster around 20 000 troops.

“Each man should have his armour

ready both day and night”

Equipment and dress

The cities military strength though did not lie in numbers but in wealth and we can see this played a major part when equipping the soldiers. Through the cities and individual burghers accounts we can see that large sums were spent on weapons and armour. Both plate and mail armour are common as well as helmets, breastplates, mailed gloves and leg armour. As for weapons one type dominates the sources and that is - just as for the peasantry - the crossbow. According to the sources it seems that the equipment the burghers used are very similar to what the nobility used. Martin Neuding Skoog have, however, examined the costs of arms and armour and compared these with the nobility's counterparts and found out that the burghers equipment were generally cheaper and of a lower quality.

Unfortunately I haven’t found any pictoral sources that clearly depict soldiers from the cities. Just as in the article about the peasantry I have found three sources of what might be soldiers from the cities or at least a good representation of what one might have looked like based on the textual evidence we have.

The drawing from Göte Göransson’s book and what I presume is the inspiration from Konga church. Source: Göte Göransson, Gustav Vasa och hans folk, p.71, Bokförlaget Bra Böcker, 1984. Medeltidens bildvärld, Historiska Museet, 2003

The first source is a church wall painting in Konga church in Skåne, which in the 16th century was a part of Denmark. The scene depicted is the Massacre of the Innocents but unfortunately the painting is quite damaged. However, we can discern two men with some of the attributes described above, they are both wearing breastplates and kettle helmets. One is armed with a sword and the other a spear. In his book “Gustav Vasa och hans folk” Göte Göransson has made a drawing of the city watch of Stockholm which looks very similar to this. The watch were made up of burghers and according to Stockholm city council protocols of the late 15th century were supposed to wear a helmet and chainmail and be armed with a sword and a poleaxe (in swedish: pålyxa). According to the same text each man in the city was obliged to own a “harnisk”, armour, which should be “ready both day and night”.

Paul Dolnstein on the right and three mounted soldiers from the Palatinate on the left. Note the different styles of helmets and that two of them are armed with crossbows. Source: Paul Dolnstein's diary, State Archives of Weimar

The next image is from german landsknecht Paul Dolnstein and depicts him on the right facing off against three mounted men from the Palatinate. The event took place during a succession war in modern south-western Germany in 1503-1505. Obviously none of the figures are Swedish or even Scandinavian although their weapons and armour correspond well to the textual sources we have. Two of the figures are carrying crossbows which would have been the main weapon of choice for the burghers as mentioned above. It also seems that their armour at most reaches as far as their knees.

Another important piece of this drawing is the horses. Martin Neuding Skoog concludes in his book that basically all soldiers from the cities would have served mounted. In battle the men most likely would have dismounted to fight but while on patrol they might have fought mounted.

The painting from Jetsmark church, very clear and uniform colours in this painting. Source: Niels Clemmensen, Aalborg Stift, Denmark

This is another church wall painting, this time from Jetsmark church in the north of Denmark. It also depicts a scene from the Massacre of the Innocents where Herod’s soldiers are looking for Jesus. The painting is a bit early for our intended period, it was painted in 1474, but I think it still gives a good idea what troops from the cities could have looked like. The tack on the horses are quite simple which might signify that they are not nobility but rather soldiers from a city. It's a bit unclear if they are wearing armour (are those coifs and are they wearing hats or helmets?) but they look almost uniformly dressed. Uniforms were not used at this time but it is not improbable that the city supplied cloth or clothing for the men since they often paid for and acquired their equipment. Being paid in cloth was common for the nobility's men so at least wearing the same colours probably wasn’t that uncommon.

Creating the burghers in miniature

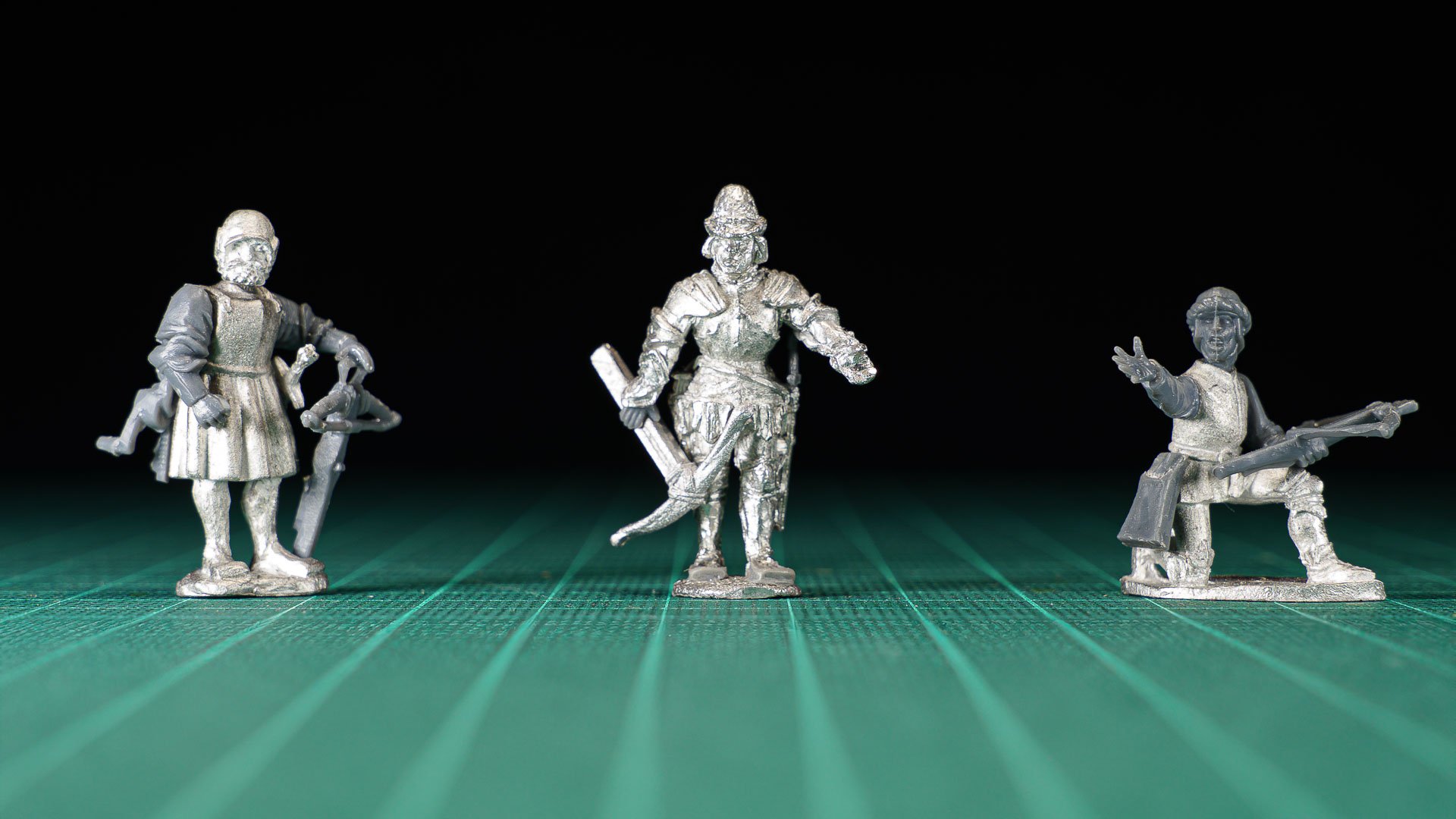

My aim was to create three miniatures based on the sources above, just as I had done with the peasantry. The first one, meant to represent the city watch, is based on a tudor dolly from Steelfist miniatures. Arms are from the Perry Miniatures “European Mercenaries” command sprue with a new hand added to the left arm so it looks like it is resting on the crossbow. The head is a burgonet, also from Steelfist miniatures, which I choose mainly because of the beard on the miniature.

The second miniature, based on Paul Dolnstein’s drawings, is a slightly converted Prince of Wales from a pack of War of the Roses Lancastrian command by Perry Miniatures. He's had his sword swapped for a new hand holding a crossbow, I also added a kettle helmet that hangs from his belt (which you unfortunately can’t see from this angle). His armour has also been filed down a bit in places, especially the elbows, to make it look more like it belongs in the 16th century rather than the 15th century.

The final miniature is based on the wall painting in Jetsmark church. The body is a retainer dolly from Steelfist miniatures with arms from Perry Miniatures plastic “Agincourt French”. The outstretched hand is from the American Civil War artillery set, also from Perry Miniatures and really shows the ease with which one can swap parts between a lot of their plastic kits. Finally the head is a sallet from Perry's “European Mercenaries” set.

The two finished units, one firing and one casually waiting.

Changes during Gustav Vasa’s rule

When Gustav Vasa took power in 1523, he began to centralize power in Sweden. He realized that there were a lot of players, both domestically and externally, that could quite easily gather enough forces to at least disrupt his rule. One way to ensure internal stability in his kingdom was to make sure that the state had a monopoly on violence. To ensure this monopoly, the state took responsibility to recruit, equip, and lead soldiers. Thus during Gustav Vasa’s rule the cities independence and distinctiveness became less and less. The state was not interested in the cities soldiers, it was interested in their wealth and what taxes they could pay. There were push backs to this but over time the cities stopped hiring and equipping their own soldiers and rather just paid a tax to let the state handle this.

I painted a total of 17 miniatures (and a few extras) to represent the burghers and based these up as two distinct units, one firing and one waiting. A suitable force these bases could represent would be the 130 soldiers that five of the cities of Östergötland were asked to muster for the campaign against Sören Norrby on Gotland in 1524. Or perhaps the men Stockholm sent with Sten Sture to fight the Russians in Carelia in 1495. Either way these miniatures constitute a considerable force of city troops on the tabletop and I doubt I will need any more for the foreseeable future.

A patrol of burghers have quickly dismounted to open fire on the approaching enemy. Karelia, eastern Finland, 1495.

A note on sources

As with my article about the peasantry, an invaluable resource for this article is Martin Neuding Skoogs book ”I rikets tjänst” which deals with the military organization in Sweden from 1450 to 1550. Another great source is the illustrator Göte Göranssons book ”Gustav Vasa och hans folk”.

Another great resource, especially for churches and church painting in Denmark, is Danmarks Nationalleksikon, for example here about Jetsmark church.